Daya Bay neutrino experiment publishes a new result on its first search for a "sterile" neutrino

The Daya Bay Collaboration, an international group of scientists studying the subtle transformations of subatomic particles called neutrinos, is publishing its first results on the search for a so-called sterile neutrino, a possible new type of neutrino beyond the three known neutrino "flavors," or types. The existence of this elusive particle, if proven, would have a profound impact on our understanding of the universe, and could impact the design of future neutrino experiments. The new results, appearing in the journal Physical Review Letters, show no evidence for sterile neutrinos in a previously unexplored mass range.

There is strong theoretical motivation for sterile neutrinos. Yet, the experimental landscape is unsettled - several experiments have hinted that sterile neutrinos may exist, but the others yielded null results. Having amassed one of the largest samples of neutrinos in the world, the Daya Bay Experiment is poised to shed light on the existence of sterile neutrinos.

The Daya Bay Experiment is situated close to the Daya Bay and Ling Ao nuclear power plants in China, 55 kilometers northeast of Hong Kong. These reactors produce a steady flux of antineutrinos that the Daya Bay Collaboration scientists use for research at detectors located at varying distances from the reactors. The collaboration includes more than 200 scientists from six regions and countries.

The Daya Bay experiment began its operation on December 24, 2011. Soon after, in March 2012, the collaboration announced its first results: the observation of a new type of neutrino oscillation - evidence that these particles mix and change flavors from one type to others - and a precise determination of a neutrino "mixing angle," called θ13, which is a definitive measure of the mixing of at least three mass states of neutrinos.

The fact that neutrinos have mass at all is a relatively new discovery, as is the observation at Daya Bay that the electron neutrino is a mixture of at least three mass states. While scientists don't know the exact values of the neutrino masses, they are able to measure the differences between them, or "mass splittings." They also know that these particles are dramatically less massive than the well-known electron, though both are members of the family of particles called "leptons."

These unexpected observations have led to the possibility that the electrically neutral, almost undetectable neutrino could be a special type of matter and a very important component of the mass of the universe. Given that the nature of matter and in particular the property of mass is one of the fundamental questions in science, these new revelations about the neutrino make it clear that it is important to search for other light neutral particles that might be partners of the active neutrinos, and may contribute to the dark matter of the universe.

Search for a light sterile neutrino

The new Daya Bay paper describes the search for such a light neutral particle, the "sterile neutrino," by looking for evidence that it mixes with the three known neutrino types - electron, muon, and tau. If, like the known flavors, the sterile neutrino also exists as a mixture of different masses, it would lead to mixing of neutrinos from known flavors to the sterile flavor, thus giving scientists proof of its existence. That proof would show up as a disappearance of neutrinos of known flavors.

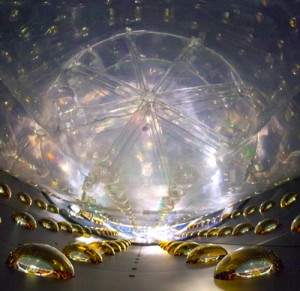

Measuring disappearing neutrinos isn't as strange as it seems. In fact that's how Daya Bay scientists detect neutrino oscillations. The scientists count how many of the millions of quadrillions of electron antineutrinos produced every second by the six China General Nuclear Power Group reactors are captured by the detectors located in three experimental halls built at varying distances from the reactors. The detectors are only sensitive to electron antineutrinos. Calculations based on the number that disappear along the way to the farthest reactor give them information about how many have changed flavors.

The rate at which they transform is the basis for measuring the mixing angles (for example, θ13), and the mass splitting is determined by how the rate of transformation depends on the neutrino energy and the distance between the reactor and the detector.

That distance is also referred to as the "baseline." With six detectors strategically positioned at three separate locations to catch antineutrinos generated from the three pairs of reactors, Daya Bay provides a unique opportunity to search for a light sterile neutrino with baselines ranging from 360 meters to 1.8 kilometers.

Daya Bay performed its first search for a light sterile neutrino using the energy dependence of detected electron antineutrinos from the reactors. Within the searched mass range for a fourth possible mass state, Daya Bay found no evidence for the existence of a sterile neutrino

This data represents the best world limit on sterile neutrinos over a wide range of masses and so far supports the standard three-flavor neutrino picture. Given the importance of clarifying the existence of the sterile neutrino, there are continuous quests by many scientists and experiments. The Daya Bay's new result remarkably narrowed down the unexplored area.

Photomultiplier tubes in the Daya Bay detectors. Credit: Lawrence Berkeley Nat’l Lab – Roy Kaltschmidt

--posted October 1, 2014

More information can be found in the published paper.